Fake feces can push ocean carbon capture to 50% of global emissions

Whale poop is precious for marine life, just like a fertilizer; this was confirmed by a German whale scientist in 2010. Victor Smetacek, his name, found that whale stools contain iron, a very important nutrient for plant growth. Before his finding, scientists didn’t take into consideration the importance of whale poop.

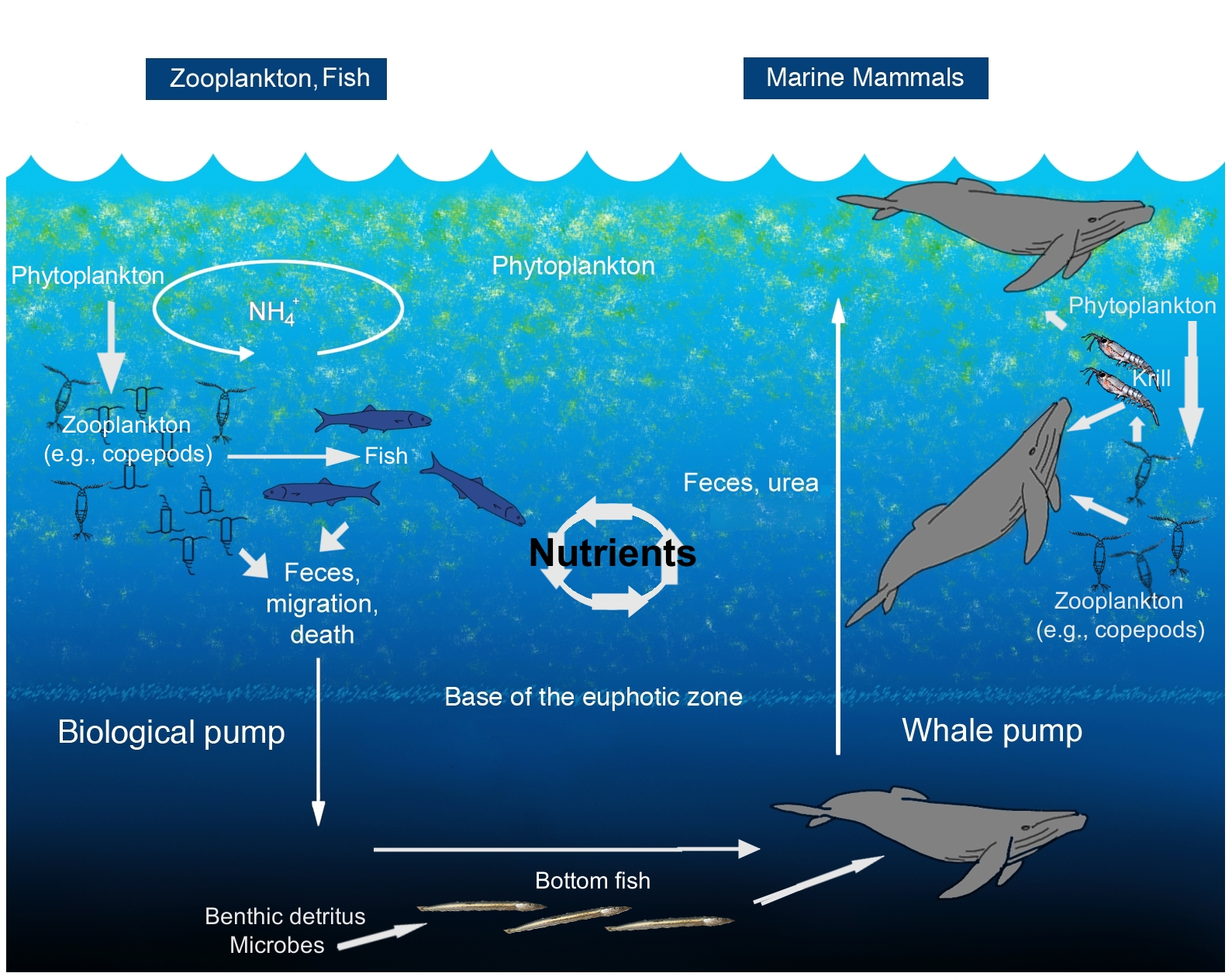

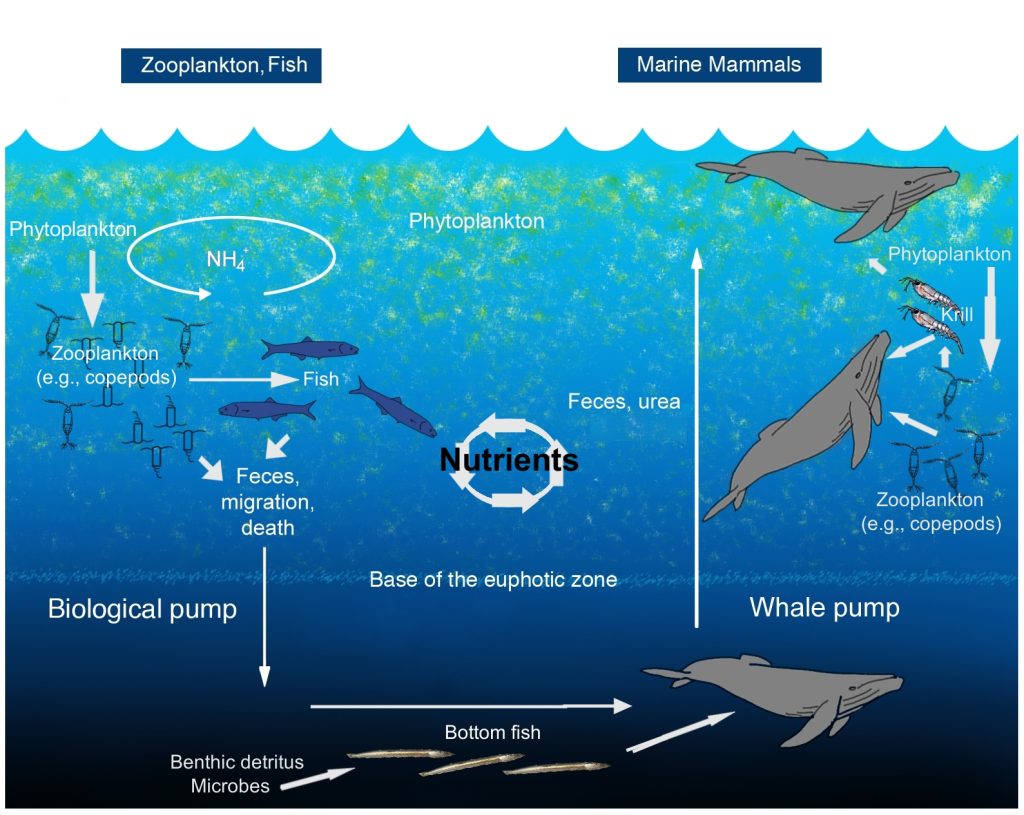

According to Smetacek’s research, while whales consume a lot of fish like krill or squids, their iron-rich excrement feeds other ocean animals. At the seabed’s surface, the nutrients encourage growth and offer food for other organisms.

Among those organisms are phytoplankton, which are the tiniest. When an area is very fertile, a phytoplankton bloom might be able to suck up carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. After feeding on the carbon dioxide, phytoplankton release oxygen in return.

Derived from the Greek words phyto (plant) and plankton (made to wander or drift), phytoplankton are microscopic organisms living in watery, salty, and fresh environments. Phytoplankton are made up of bacteria, protists, and mostly single-celled plants. Cyanobacteria, silica-encased diatoms, dinoflagellates, green algae, and chalk-coated coccolithophores are some of the most prevalent types. Phytoplankton, like terrestrial plants, has chlorophyll that captures sunlight and converts it to chemical energy through photosynthesis.

When we burn fossil fuels, our oceans absorb 30% of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. However, an international study group wants to explore whether it’s possible to push that percentage even higher by artificially encouraging phytoplankton growth with fake whale feces and increasing the oceans’ carbon-capture capacity to 50%.

Professor Sir David King, the Chair of Cambridge University’s Centre for Climate Repair, is responsible for this research. According to King, the approach might result in the oceans absorbing 2 to 20 billion tons of carbon gases per year. Human activities emitted around 34 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2020, so if King’s predictions are true, the oceans might absorb more than half of our yearly global greenhouse gas emissions.

King and his team plan to begin their research in southwestern India. Their fake whale feces will contain nitrates, phosphates, silicates, and iron, just like the real one. Scientists will make it out of natural elements like volcanic ash or desert sand. Then rice husks, from a factory in Goa, will be used to store the artificial poop on the seabed’s surface.

In the first experiment, they want to see how well the husks carry the poop and plan to conduct additional tests in several of the world’s oceans once those tests are completed. Anyway, they don’t just want to throw a bunch of chemicals into the water but to learn something from artificial fertilization.

“Most of our farmland is devoid of earthworms, which is ridiculous”, says King. “Earthworms do all the plowing for us in a very gentle way”.

Experiments reveal that earthworms help water penetrate into the soil in a way that is beneficial to plant growth, according to King. However, studies demonstrate that water is not absorbed by the soil on land fertilized with artificial compounds that kill earthworms, and crops die as a result.

“We don’t want to create those problems in the oceans”, adds King.

However, the experiment didn’t completely satisfy some scientists. While Smetacek’s discovery of whale feces in 2010 was significant, it’s still unclear how essential whale poo is for ocean fertilization and carbon capture, while others say King’s idea isn’t completely new.

“Whale poo is just another flavor of macronutrient fertilization”, wrote Andreas Oschlies, a program director at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center.

Macronutrients are what an organism needs in enormous quantities.

“And all suggestions regarding nitrogen fertilization have, as far as I know, neglected feedbacks in the nitrogen cycle, which will likely reduce or in some regions reverse the intended increase in [carbon capture]”, wrote Oschlies.

Artificial fertilization, according to Oschlies, has a negative impact on other environmental systems.

“Dumping huge amounts of nutrients into the ocean will increase demand and, eventually, costs for nutrients worldwide, also making food more expensive”, he wrote.

According to King, his team has evaluated the issue and is considering using naturally existing materials. But, he argues, there’s still a long way to go; first, they have to see if the experiment works at all.

Source dw.com