Plectranthus barbatus can become a new sustainable toilet paper

A lush plant sways over the landscape of Meru, a town in eastern Kenya. Benjamin Mutembei, a resident of Meru, is cultivating this plant, called Plectranthus barbatus which is used for toilet paper rather than food.

In 1985, he started growing the plant. “I learned about it from my grandfather and have used it ever since. It’s soft and has a nice smell,” he says.

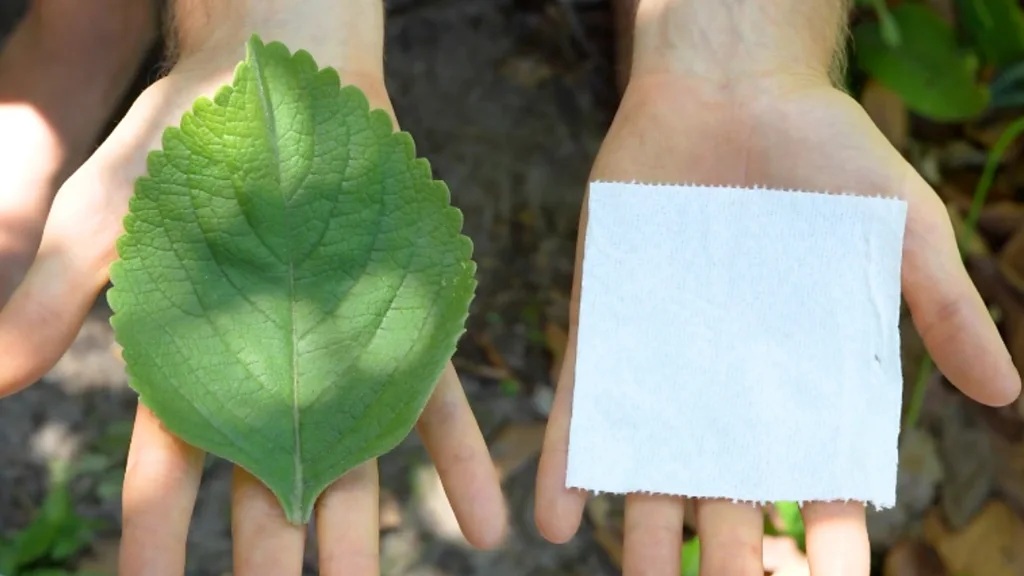

As reported here, the leafy plant Plectranthus barbatus can reach a height of 2 meters (6.6 feet). Its leaves have a minty, lemony scent and are about the size of a square of industrial toilet paper. The leaves are delicate and covered in small hairs. This plant is extensively grown throughout Africa and is occasionally used to mark property boundaries because it does well in warm tropical temperatures and partial sunlight.

“This has been an African tissue for a long time, and everyone in my household uses the plant. I only buy modern toilet rolls when the leaves have all been plucked,” Mutembei says.

In Kenya, the plant has given Mutembei an affordable substitute for buying toilet paper. Similar to many other commodities, toilet paper has become more expensive throughout Africa, primarily as a result of the high cost of imported raw materials like wood pulp, which are necessary for making toilet rolls. According to the Kenya Association of Manufacturers, the cost of raw materials now accounts for 75–80% of the total cost of tissue products in Kenya.

The world market is dominated by toilet paper produced from virgin wood pulp. “Typical toilet paper is made of 70-80% short fiber hardwood and 20-30% long fiber hardwood,” says Ronalds Gonzalez, a professor in the Department of Forest Biomaterials at North Carolina State University.

According to research by the environmental impact consultancy Edge, an estimated one million trees are felled annually worldwide to produce toilet paper.

The pulp and paper sector uses about 35% of harvested trees to make paper, making it the greatest consumer of virgin wood in the world. According to the most recent Ethical Consumer research on ethical toilet paper, this is causing global ecosystem disruption, deforestation, biodiversity loss, soil erosion, and species extinction.

According to Martin Odhiambo, a herbalist specializing in traditional plants at the National Museum of Kenya, there may already be a solution to the environmental harm caused by the cutting down of trees for toilet paper.

“Plectranthus barbatus is the African toilet paper. Many young people nowadays are unaware of this plant, but it has the potential to be an environmentally friendly alternative to toilet paper,” he says.

Although the real number of individuals in Kenya using the plant as toilet paper is unknown, Odhiambo notes that it is still widely produced throughout Africa and is still employed in many rural places where it is easily available.

It takes 1-2 months for Plectranthus barbatus to reach its maximum height after a cutting, which costs about 50 Kenyan shillings ($0.37).

“The leaves are similar in size to an industrial toilet paper square, making them suitable for use in modern flush toilets or for composting in latrines,” says Odhiambo.

Visitors from across Kenya attend Odhiambo’s lectures on the uses of Plectranthus barbatus and buy cuttings from his botanical garden at the National Museum of Kenya in Nairobi.

“My class has grown to over 600 participants. People are enthusiastic about learning how to use the plant and often ask for cuttings and seedlings to take back to their towns,” he says.

Other nations are also investigating the plant’s potential.

For five years, Robin Greenfield, an environmentalist who operates a non-profit organization in Florida that promotes sustainable living, has been employing the leaves of Plectranthus barbatus.

Greenfield grows more than 100 Plectranthus barbatus plants at his Florida nursery and organizes a “grow your own toilet paper” initiative. He encourages individuals to grow their own toilet paper by sharing cuttings for free or in exchange for voluntary donations. He claims to have given cuttings to hundreds of people thus far.

“There are many people who associate using the toilet paper plant with poverty,” says Greenfield, though he points out that industrial toilet paper is ultimately made from plants too.

Greenfield reports that those who use the plant have given him excellent feedback. “For anybody who feels a little hesitant to try this plant, I would say to drop your worries about what people think about you. And simply by saying, ‘I’m going to be me, and that might mean wiping my butt with some really soft leaves that I grow,'” he says.

However, how likely is it that this plant will be employed more extensively?

Production on a large scale has not yet been investigated. Rather, companies like WEPA, one of the biggest producers of toilet paper in Europe, are taking other measures to lessen the environmental effects of traditional toilet paper. According to a spokesperson, WEPA has created a novel technique for making toilet paper out of recycled cardboard that does not require bleaching the fibers.

Before being made into paper, wood pulp is usually bleached, releasing chlorinated compounds into the atmosphere. According to a report by the non-profit Natural Resources Defense Council, these compounds can react with carbon-based materials to produce dioxins, which are extremely dangerous substances linked to cancer and other health risks.

The toilet paper plant, meanwhile, is expected to have a “minimal” impact on the industry, says a WEPA spokesperson.

One drawback is that wastewater and disposal systems, especially in Europe, aren’t designed to handle this type of paper, as only soluble items can be flushed through the system, the spokesperson says.

Greenfield says that’s where compost toilets come in. “I use a compost toilet. The leaves go back to the earth and produce soil, which can then support food growth. It’s a closed-loop system, and I think using these leaves could lead us to a conversation about the environmental benefits of composting.”

There are also limitations on the locations and countries where Plectranthus barbatus can be grown, says Wendy Applequist, an associate scientist at the Missouri Botanical Garden. In South Africa, for example, Plectranthus barbatus is regarded as an invasive species, and growing or selling it is banned. Invasive species cost the global economy more than $423bn (£333bn) every year and are a major driver of biodiversity loss.

According to Applequist, environmental concerns may be reduced by cultivating the plant in a designated setting within a specified region and keeping an eye on its development to prevent it from spreading into the surrounding ecosystem. However, public acceptance continues to be perhaps the largest obstacle to mainstreaming. However, Odhiambo is optimistic about his Nairobi plant nursery.

“I know some people see using leaves as toilet paper as a step backward, but understanding the benefits of this plant, I believe it could become the next green alternative,” says Odhiambo. “I’ve been growing it in my nursery and sharing it with communities across Kenya, and people have been amazed by its convenience. If we keep an open mind and continue promoting this plant, we could eventually mass produce it for widespread use.”