It doesn’t require water or a sewer connection

Few people can arouse passion in others over a toilet. Diana Yousef is among the very ones who can. She exhibits this in every speech she conducts to possible funders or investors, in every media interview, and even in a TEDx lecture hosted at her daughter’s school.

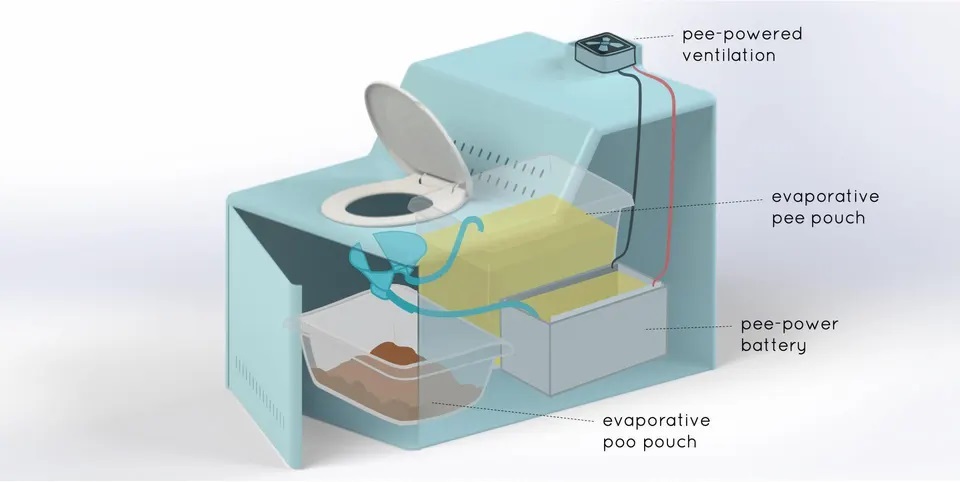

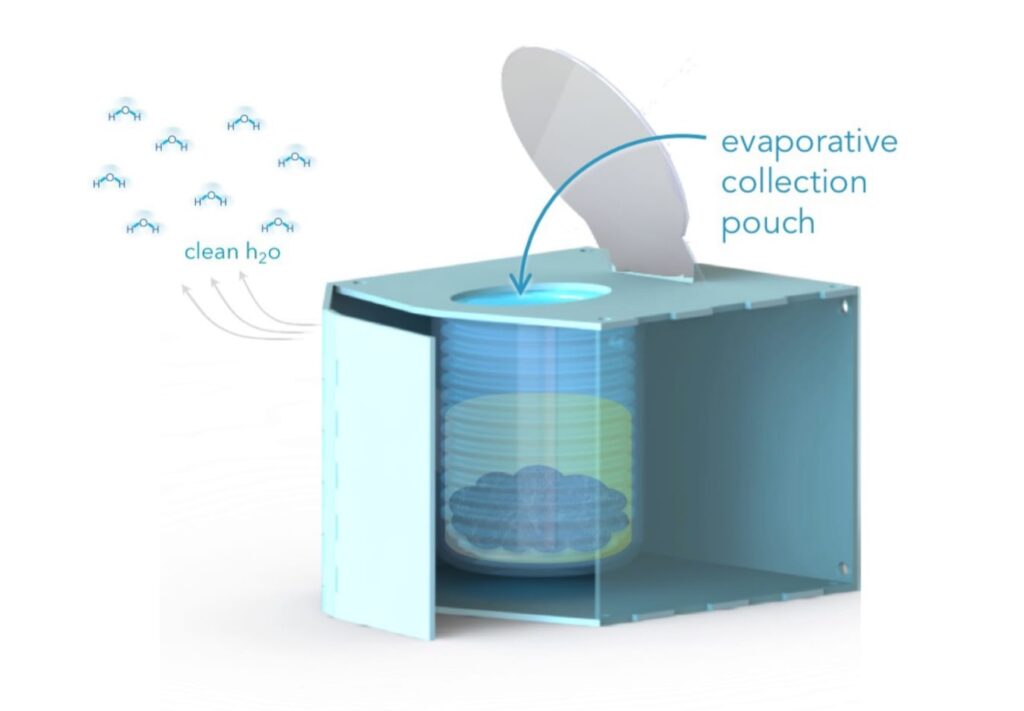

As reported here, Yousef, an Egyptian immigrant who was born in Boston and has a PhD in biochemistry from Cornell University, invented a toilet that runs without water or a connection to the sewer system. It works by a membrane that removes 90% to 95% of waste by evaporation.

The concept aims to address inadequate sanitation, which is a serious issue for half of the world’s population. This has several negative effects, such as fatalities from infectious diseases, environmental issues, and—this one particularly moves Yousef—violence against women and girls for going outside their homes to relieve themselves.

“When people live without access to safe sanitation, it’s very difficult for them to improve their quality of life,” Yousef said, in a video interview from her home in Boston.

The World Health Organization estimates that 4.2 billion people employ sanitation services that don’t treat waste. Of them, 673 million are compelled to defecate outside since they lack access to any kind of bathroom. Every year, infections associated with inadequate sanitation cause around 564,000 deaths, primarily from diarrhea.

“But beyond that, one of the things that moves me the most is the disproportionate way in which [a lack of adequate sanitary services] harms women and girls, who don’t have access to safe private toilets near their homes. There’s a huge, little-discussed problem of women being raped—and even murdered—simply because they need to go to the bathroom,” Yousef explains.

“50% of schools in the world lack adequate sanitation facilities, which makes it extremely difficult—for girls especially—to go to school. When they go to school, they fight the urge to go to the bathroom, so they don’t eat, they don’t drink, they end up tired, and they have trouble paying attention. And, when they start having their period, they miss a week of school every month and fall behind.”

Yousef, a mother of three daughters, ages thirteen, eight, and five, bemoans the state of the situation: “I find it very difficult to understand that this happens to girls all over the world, while my daughters have the life they have just because of where they were born.”

One of the things that motivated Yousef to create her startup for change: WATER Labs, was the birth of her children. “When I had my first daughter, I was out of work for two years, because nobody wanted [to hire] me.” As a result, she had to reinvent herself. “I want to set an example for them, to show them that they can do whatever they want, that they have the ability to decide.” Her work also incorporates elements of her Egyptian background. “I think that all of us who come from the Middle East are very aware of the importance of water. It’s vital.”

She picked up an idea that had come to her while working as a consultant for NASA and USAID in 2009 on a collaborative project that looked for technology solutions to issues with access to water. This idea took into consideration recycling wastewater and converting it to potable water through the use of breathable materials.

“These materials have the property of absorbing moisture from one area and passing it into the dry air on the other side. The liquid water enters the material and comes out the other side as vapor,” she describes.

Her prior work with the UN allowed her to go to countries in the Global South and learn about issues with sanitary infrastructure. Her job includes looking for business models that connect the private sector to the field of development.

It appeared that the breathable material was a very low-energy solution that could be applied on a large or small scale. In underdeveloped areas with little infrastructure, it might be quite helpful. “I realized that it was probably better to use [this method] to get rid of dirty water, rather than to make clean water.”

At MIT, Yousef presented her own project for the first time, meeting experts who were intrigued by the concept. Some joined her team, which consists of seven members at the moment. She had access to a laboratory where she could turn the notion into a reality because of an initial grant of $50,000.

The prototype project was implemented in February 2020 in a Kiboga, Uganda refugee host community, funded by the international government initiative Humanitarian Grand Challenges. About 400 people a week used the two Turkish-style restrooms that were constructed in a women’s hospital and a girls’ school (they were on the floor and did not have seats). “We saw that they contained the waste completely, in a hygienic way. We didn’t detect any smell in the [bathroom]. Additionally, maintenance only needed to be done once every two or three weeks.”

The second pilot project is being implemented in Kuna Naga, a suburb of Panama City without sewage or running water that is home to the Indigenous Kuna people. Asocsa, a nearby construction company that typically works in low-income areas, is providing funding. Two Western-style sit-down toilets were placed in two households in October 2023, accommodating a combined user count of approximately 25.

The membrane simply starts to evaporate water from pee and poo when it comes into contact with them; there is no flush system. “We’ve been able to show that we can run these toilets for two, even three months, without having to empty them.” The installation of public restrooms in the same community is the next scheduled stage.

Yousef predicts that the final price of the iThrone, which took home the MAPFRE Foundation Award for Social Innovation in the Health Improvement and Digital Technology category, will be approximately $200 per device.

“We plan to outsource production to local partners, so the price will come down even further. Other solutions that are used cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is much cheaper and simpler because it doesn’t require a lot of infrastructure, but it offers high performance by making the waste disappear on-site,” she explains.

Yousef continues saying that most of the waste that does not evaporate and the bag—made of permeable material—are compostable. So, when emptying the toilet, the waste “can be disposed of in whatever way the partner [organization deems fit]. If it’s a humanitarian organization [operating] in a crisis or a refugee camp—without the capacity to build adequate sanitation infrastructure—they just burn the waste. But in a community that wants to make sanitation circular, the waste can be converted into something with value, [such as] fuel or fertilizer.”