Poop as a time capsule

During the Late Triassic period, in today’s Poland, a dinosaur ate a big meal of green algae and then took a poop. Then, roughly 230 million years later, those fossilized feces revealed an entire family of undigested beetles.

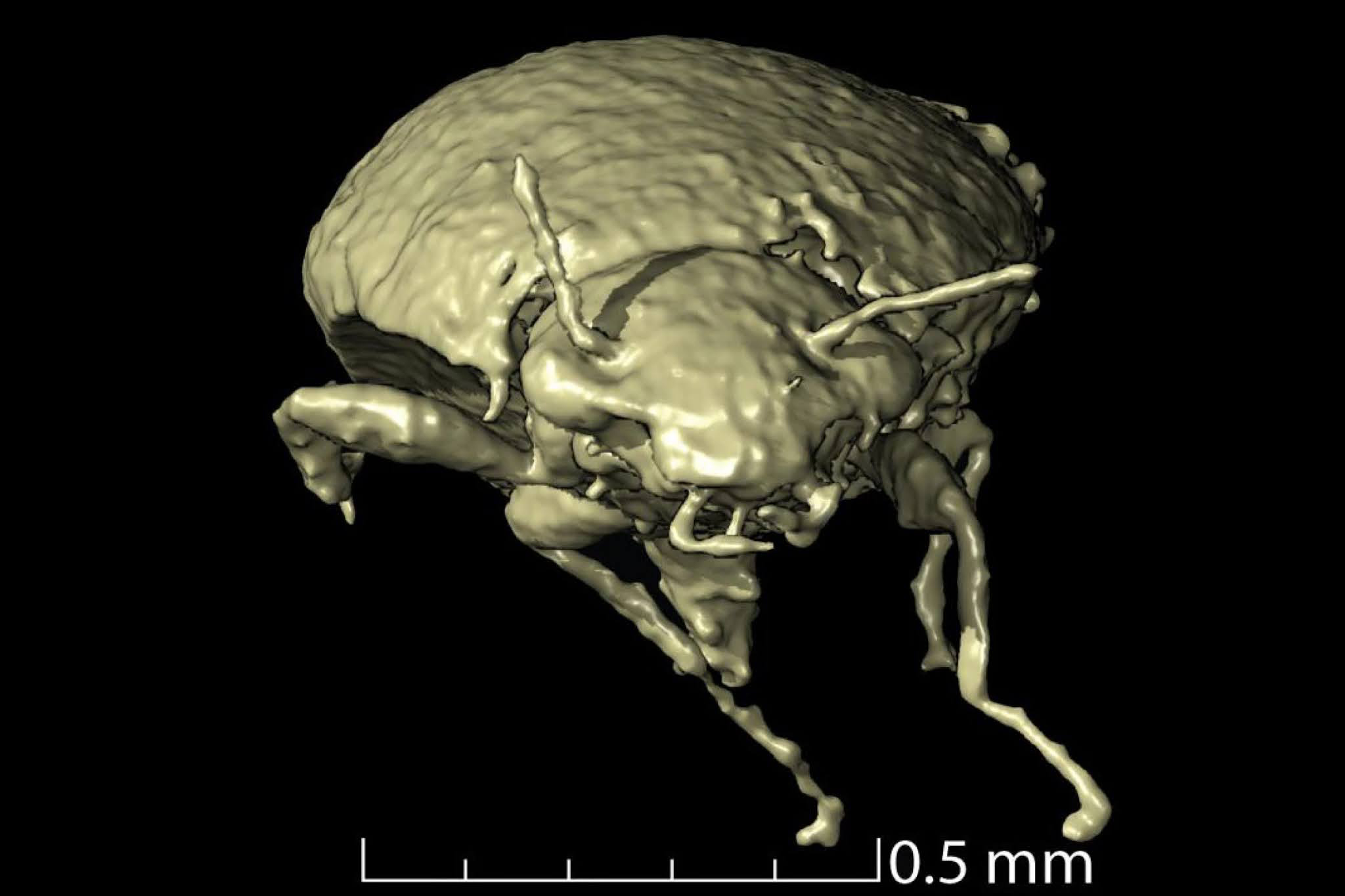

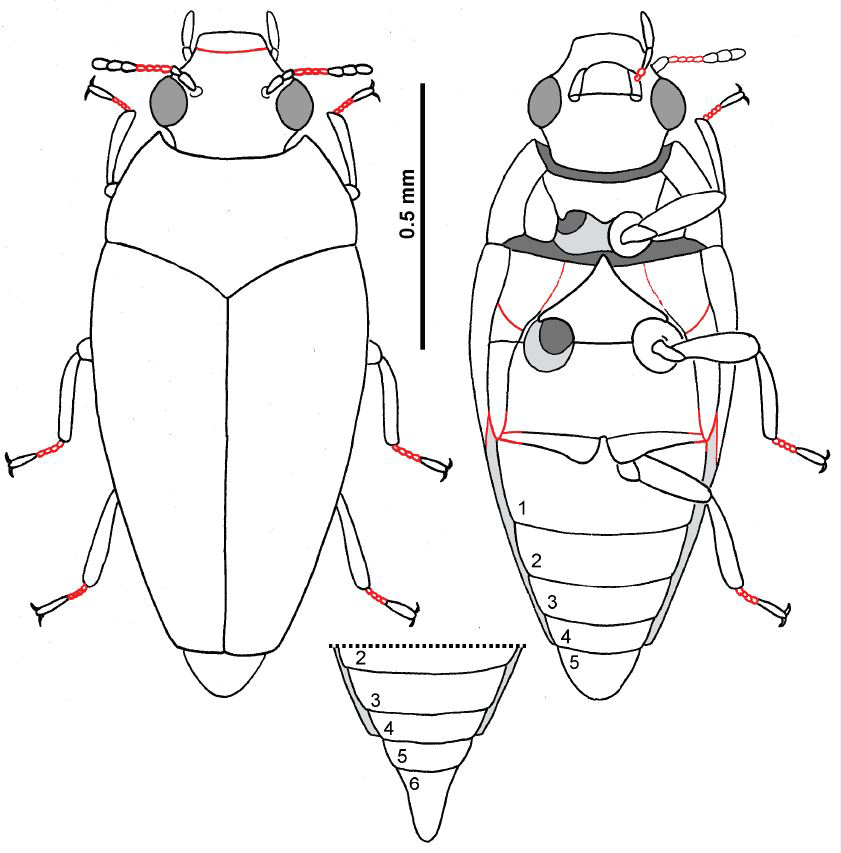

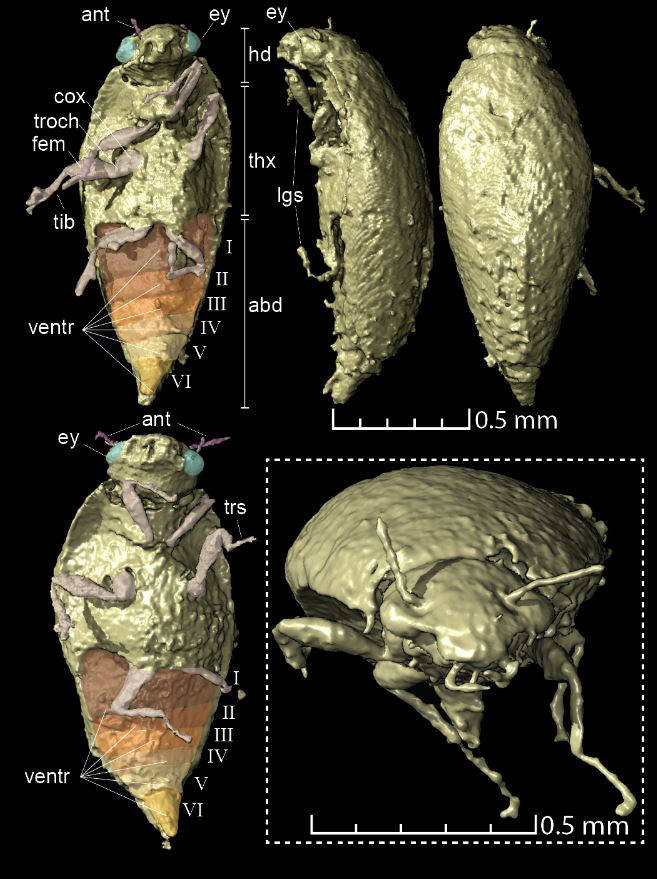

These insects are the first to be described from fossilized feces, and they are unlike anything discovered in amber before. They are more ancient, and their legs and antennae are also intact. So researchers were able to accurately reconstruct their three-dimensional shape and form. The new species has been named Triamyxa coprolithica.

“I was really amazed to see how well preserved the beetles were when you modeled them up on the screen; it was like they were looking right at you”, says paleontologist Martin Qvarnström from Uppsala University in Sweden.

The Triassic is considered a crucial period for insect evolution, especially for beetles, which are the most diverse order of organisms on Earth today. Unfortunately, many beetle fossils from this time only give us an imprint of the species, not a three-dimensional view. Amber deposits are the exception; however, these usually date no further back than 140 million years.

The beetles found in dinosaur poop are nearly twice as old. After close analysis, researchers placed the new species of beetle in the Triamyxidae family. Given certain resemblances, they suspect the bugs are an extinct offshoot from a small suborder of beetles known as Myxophaga, which has a sparse fossil record.

Modern myxophagan beetles can be found in great numbers on green algae mats, typically near water, and the discovery suggests that their ancient relatives may have thrived in similar aquatic habitats.

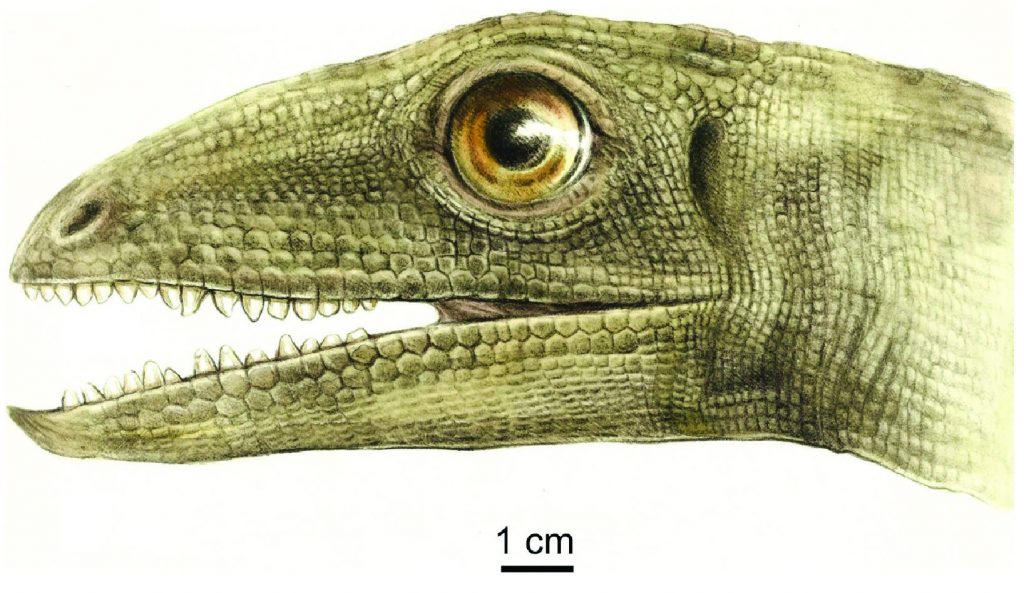

The fossilized poop, known as a coprolite, is thought to have come from a two-meter-long dinosaur called Silesaurus opolensis, which mainly eats plants but also appears to have a penchant for insects.

Because these insects are so small and numerous, scientists think they weren’t the main meal.

Researchers think the beetles would have had a better chance of surviving dinosaur digestion compared to other insects because they have hardy and tiny bodies. Anything with a soft body would have been easily broken down.

“Although Silesaurus appears to have ingested numerous individuals of T. coprolithica, the beetle was likely too small to have been the only targeted prey”, explains Qvarnström.

“Instead, Triamyxa likely shared its habitat with larger beetles, which are represented by disarticulated remains in the coprolites, and other prey, which never ended up in the coprolites in a recognizable shape. So it seems likely that Silesaurus was omnivorous and that a part of its diet was comprised of insects”.

The discovery had scientists thinking coprolites could make excellent proof of early insect evolution. Fossilized feces might be harder for the human eye to see through, but using micro CT scanning, researchers could make out all the tiny details on T. coprolithica.

“In that aspect, our discovery is very promising, it basically tells people: ‘Hey, check more coprolites using microCT, there is a good chance to find insects in it, and if you find it, it can be really nicely preserved'”, says entomologist Martin Fikáček from the National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan.

It took until the Early Cretaceous for tree resin to be abundant enough to capture early insects in action and fossilize them. During the Triassic, there was far less tree resin around, which means we don’t have amber deposits to tell us what insects looked like at this time.

“Maybe, when many more coprolites are analyzed, we will find that some groups of reptiles produced coprolites that are not really useful, while others have coprolites full of nicely preserved insects that we can study”, he says.

Source sciencealert.com